I ALWAYS TRY TO READ the readings for Mass ahead of time, so that I can reflect on them as part of my preparation for attending the Holy Sacrifice. This is a practice that I was taught many years ago and have tried to make a daily habit, so that even on days when I don't attend Mass I read and meditate on at least a little bit of Scripture. When I reflect on what I have read, I try to discern, amongst other things, how these readings complement one another (usually the OT and Gospel strike similar chords) and how they illuminate God and His will for us; this, in turn, leads to thoughts of how this message reflects on the Christian life and my own life in particular.

Sometimes I find that the preacher at Mass will touch on at least one of the things I noticed during my preparation, and at other times he may draw my attention to something that had not occurred to me. Occasionally, though, I find that the homilist treats the readings simply as a springboard for some other topic. On such days, I sometimes finding myself composing in my head “the sermon I wish I’d heard.” This past Sunday, the Second Sunday of Lent, was such a day.

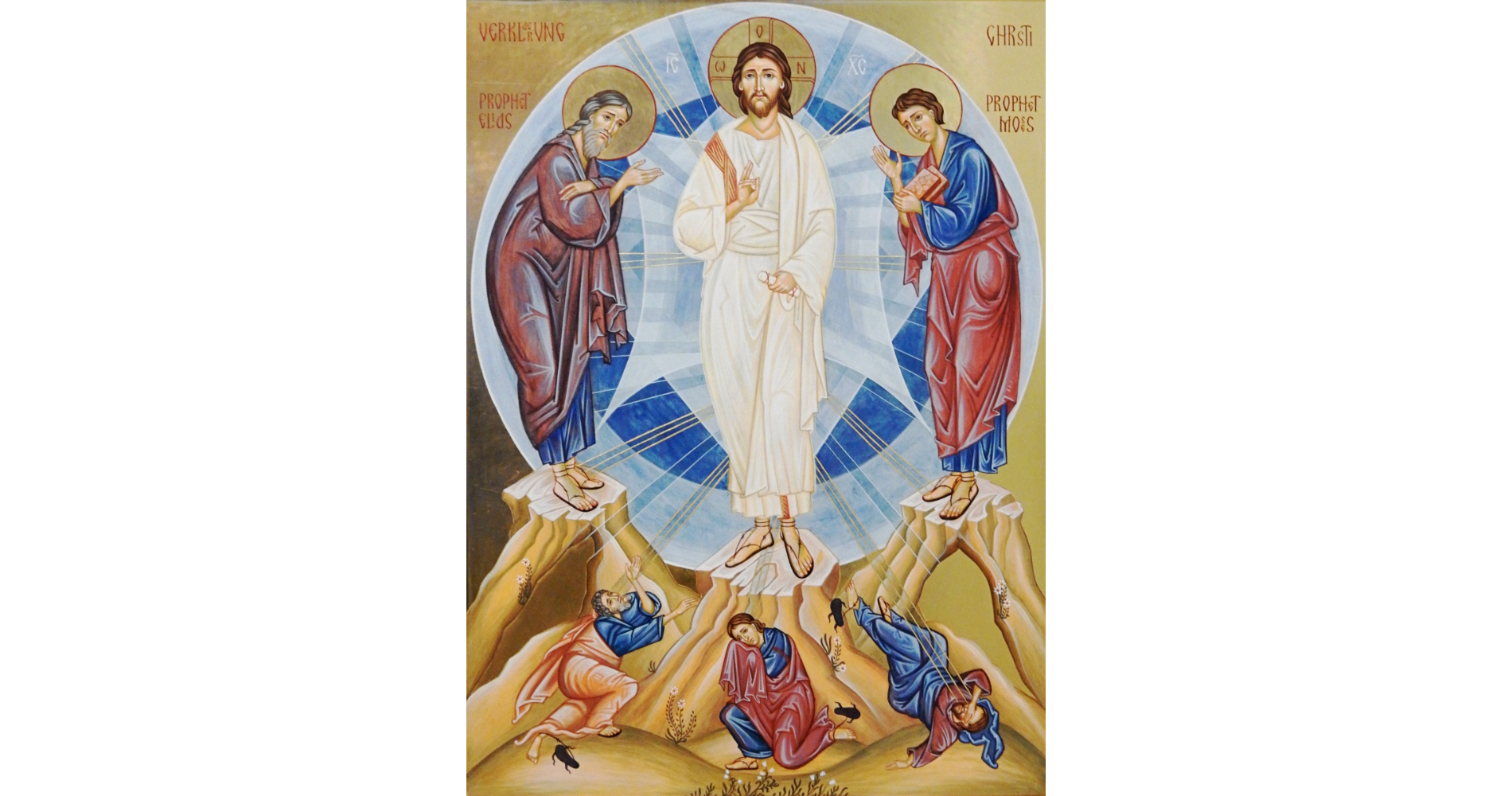

Transfiguration

On that day, the Gospel reading was St. Luke’s account of the transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor. The preacher at Mass was so eager to get to the topic he had in mind (which was not the transfiguration of Christ) that he made a careless mistake, one that (fortuitously) got me thinking more deeply about the day’s readings and what they show us about God and our human condition.

The mistake he made was to hurriedly equate the transfiguration of Christ with the transformation every Christian must undergo before entering eternity. While it is true that Christ was transfigured and that every Christian must be transformed, these are two very different things, and it takes a bit of work to see what one has to do with the other. The figura in transfiguration refers to a change in appearance, while forma in transformation refers to the kind of thing something is. Therefore, transfiguration is a change in appearance without a change in kind, while transformation is a much more fundamental kind of change, from one kind of thing into another.

The main point of the Transfiguration account is that Jesus allows his closest associates to see Him as He really is: not merely a man, but also God. It's not clear that Peter, James, and John recognized the two figures standing with Christ (it seems more likely that they were told later that these were Moses and Elijah), but they clearly recognize Jesus, despite the fact that his face was “altered” by the glorious light radiating from it. In other words, although His appearance had changed, they still saw the Jesus they knew. He was not “transformed,” but simply seen for the first time in the light of His divine glory.

This is not to say that the three apostles instantly recognized the significance of Jesus' changed appearance. When Peter sees Jesus transfigured and conversing with Moses and Elijah, his first impulse is to prolong this marvelous experience by pitching tents for the three , as if to honor noble guests. I suppose we shouldn’t blame him for his unthinking proposal. After all, both his mind and his eyes must have been dazzled by the blinding light emanating from the One “in Whose light we see light itself.” Just then, though, as if to make sure the three apostles do not misunderstand the significance of what they are seeing, a cloud descends to obscure their vision, as God the Father Himself speaks: “This is My Son, My Chosen One. Listen to Him.” The Father Himself cannot be seen (cloud) but His Son can (light). In other words, the entire event is intended to make clear that Christ is both Man and God.

Typology of Light and Darkness

This alternation of brilliant light followed by a dark cloud account reminds me of the “mandorla” or cloud of glory that surrounds images of Christ in traditional iconography, which I’ve mentioned before: the outer edge of the nimbus is dazzling white but grows darker toward the center, where Christ Himself is, indicating that the closer we come to Him and the better we know Him, the less we can truly grasp with our minds the immensity of Who He is. (Notice that in the image that accompanies this post, the mandorla has been altered to emphasize the glory streaming from the person of Christ.) Seeing Jesus in dazzling light, the apostles assume that the equal of Moses and Elijah, but they must enter the “cloud of unknowing” where the ineffable God dwells to learn that Jesus is True God as well as True Man.

Understanding the significance of Christ’s transfiguration allows us to recognize the connection between this Gospel passage and the Old Testament reading of the day (Genesis 15), which describes God solemnizing His covenant with Abraham. The Almighty uses a ceremony that Bible scholars tell us was customary in Abraham's day whenever two men entered into a binding covenant or contract with one another: they would sacrifice animals, split them in half and then walk between the two halves, to indicate that covenant would remain binding until the halves should be rejoined and restored (in other words, forever, since dead animals can’t be revived).

Of course, in this case, one of the parties was God Who, being pure spirit, could neither be seen face to face nor walk between the halves of the sacrifice. Therefore, the smoking pot and flaming torch that pass between the halves of the sacrificed animals are tokens of His presence and his participation in the covenant. In the darkness of the night, Abraham can clearly see these signs.

Why a smoking pot and a flaming torch, though? The full significance of those choices could not have been apparent to Abraham, although his descendants centuries later might have recognized their similarity to the signs that accompanied the Israelites through the wilderness to remind them that God, not Moses, was their true leader: a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. The sign was immensely bigger in the Exodus account, because it needed to be visible to hundreds of thousands of Israelites, but it is essentially the same sign as that given to Abraham, a single man alone in the night with God.

The smoking pot and flaming torch that Abraham saw prefigure the greater signs that would reassure Abraham's posterity (the Israelites) that God was still keeping His covenant with them. In light of this, we can also recognize that the signs that accompanied Moses, in turn, prefigure what Peter, James, and John experience on Mount Tabor when they see Christ's glory revealed and hear the Father speak from the cloud. The torch that Abraham saw and the pillar of fire that lit up the night for the wandering Israelites both prefigure the dazzling light of Christ’s divinity (Whom we can see) on Mount Tabor, just as the smoking pot that Abraham saw and the pillar of cloud that led the Israelites during the day prefigure the “cloud of unknowing” that descends upon the apostles as they hear the invisible and ineffable God of Heaven declare Jesus to be His beloved Son. As Jesus said, “He who has seen Me has seen the Father.”

In each of these three instances, first with Abraham, then Moses, and finally the three apostles, the same truth is represented, using similar signs. The signs indicate that God remains faithful to His covenant forever, no matter how many times His chosen people betray Him or believe that He has forgotten them. On the day of the Transfiguration, as it happens, one of Jesus' chosen band is about to betray Him in the most heinous way possible: by delivering Him to those who will torture and kill Him. The purpose of the Transfiguration, however, is to let Peter, James, and John know in advance that things are not what they seem: Jesus is not merely a man, He is immortal God. He will suffer and die, as all men do, but His rising from death will reveal His glory and open the way of everlasting life to all mankind. In this way, Christ’s eternal divinity will be revealed not only to Peter, James, and John but to anyone who has eyes to see. On Mount Tabor, the dazzled minds of the apostles cannot yet grasp this truth, nor will they do so, until they see the risen Christ and He explains how He has fulfilled all the things that were foretold in the Old Testament.

By the way, the kind of foreshadowing or prefiguration I've been describing usually goes by the name of typology, and is the most ancient form of Biblical exegesis; the resurrected Christ Himself used typology to explain to his disciples how Scripture had foretold His coming (even His suffering and death) and to assure them that He is the long awaited Messiah God had promised through His prophets.

Transformation through Purification

This brings us to the second point, which the priest I mentioned earlier sought to connect to the transfiguration: everyone who hopes to enter the Kingdom of Heaven must be transformed into the likeness of Christ. This transformation may have outward signs in the way we behave, but it begins invisibly, interiorly, and those interior actions of grace in our souls gradually move us to behave differently. Others who know us well may notice changes in our behavior or demeanor as we become more Christlike, but being a Christian is not simply a matter of changing our ways; it is, in fact, a fundamental change in who we are. We must not simply become more loving, but must be transformed into Love, as Christ is Love, as God is Love—perfect Love.

“Be perfect, as your heavenly Father is Perfect,” Jesus said to His disciples. When we hear that, we may think that this is impossible, something we can never achieve. And, in fact, we cannot do it. We cannot remake ourselves any more than we could have made ourselves to begin with. We may like to believe that we are self-sufficient, but that mistake is as old as mankind; it is the lie the serpent told Eve, to persuade her to ignore God’s loving command and instead try to make herself a god through disobedience. This lie is one that many will continue to believe until the end of time. But we Christians should know better; we should know, first, that we are called to perfection but, second, we cannot achieve perfection through our own efforts. It requires God’s superabundant Grace to effect this transformation. And it will take time—all our earthly lives, if not longer—before we are fit for eternity.

Now: what, if anything, does Christ's Transfiguration on Mount Tabor have to do with us? The typology that links the Gospel account to the reading from Genesis shows not only that Jesus Christ fulfills the Law, the Prophets, and indeed the covenant made between God and Abraham and his descendants but also that He IS the very God Who who first made that promise. Jesus reveals his true nature to the three apostles so that they will not be disheartened by His approaching death, but He is also foreshadowing the fact that they, too, have a similar destiny. Although, like Him, they will have to suffer and die, this is necessary because, to claim that immortal destiny, they must first become like Him. In other words, the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor itself prefigures the ultimate destiny of all who follow Christ, a destiny that is signified by His death and Resurrection but which is finally realized only when all have died and risen, at the End of Time.

This prefiguration is meant to encourage us all, because being transformed into the likeness of Christ is not the work of an instant (although it begins at the moment of our baptism). As we can see in the examples of the apostles, even those who lived in continuous close proximity to Jesus for three years—spending every waking (and sleeping) hour with Him, constantly learning from Him—needed time to be transformed into His likeness. The Acts of the Apostles and the epistles of St. Paul and other apostles testify that even those who knew Christ best and loved Him most had to undergo many trials and endure a process purification that involved much suffering. But that painful process remade them into “new men.” Like gold refined by fire, they were purified and cast into a new form, the form of Christ. We see, for instance, that Peter, who had protested the very suggestion that Jesus had to die and who fled into hiding when He was condemned to death, later was able to heal a cripple and even raise the dead in the name of Jesus and, later still, he willingly accepted crucifixion in imitation of his Risen Lord .

This process of transformation, then, is quite different from transfiguration. It does not reveal something innate in us—for we lost our likeness to God when mankind fell through the disobedience of Adam and Eve—but it changes us fundamentally, from being creatures doomed to death into new men fashioned into the likeness of the immortal Son of God. This transformation is achieved with our voluntary cooperation, our willingness to suffer for the sake of Christ, as He did for us—but primarily, through God’s Grace, which alone can achieve what we could never do for ourselves. Unlike pagan philosophers, who strove to perfect themselves through their own efforts, Christians know that “we have no power in ourselves to help ourselves.” We must rely on God to breathe the transforming fire of His Holy Spirit into us, to melt down the substance of what we were and, like gold purified in a crucible, to burn out all the dross of our wayward wills and finally, only when all impurity has been removed, to pour us into the mold of His Son.

The process of our transformation begins at Baptism, which cleanses us of Original Sin and gives us a new life in Christ, but it continues throughout our lives as we learn to submit ourselves to God’s will and to be transformed by His Grace. For most of us, even after death the process will continue as the cleansing purgatorial fire completes our perfection until finally we are fit to stand in the presence of God, where “we shall be like Him” (see I John 3:1-3).

Saint Athanasius, best known for asserting the divinity of Christ as well as His humanity, famously said that “God became Man, so that men might become gods.” This may sound like an audacious, even outrageous claim, yet it is the central truth of the Christian faith: we are destined for eternal life, but to enter eternity we must become like God, perfect Love. In fact, the whole purpose of this earthly life is to be transformed into the likeness God, to become Love. This holy season of Lent is intended to help us toward that goal: to reflect on our sins and weakness, so that we will learn to rely on God’s transformative grace. As we learn to deny ourselves, we become less, so that He may become greater in us, until finally “Christ is all in all.” Then we will see Him as He is, with eyes no longer dazzled by His glory because we will have been made glorious with Him. This is more than anything we could ask or imagine, yet it is what God wills for us.

The account of Christ's Transfiguration should encourage and reassure us as well as the apostles who accompanied our Lord to the height of Mount Tabor. Our transformation will not happen in the twinkling of an eye, but it will happen by God's grace, if we persevere and do not lose heart.

I pray that this Lent, encouraged by the Transfiguration of Christ, we will all embrace the crosses of our lives gratefully and willingly, knowing that the Way of the Cross is the only way that leads to eternal glory with God in Christ.

• • •

BY THE WAY, if you would like a reliable source of sound, well-developed, easy-to-understand homilies by actual priests (not lady bloggers) who are licensed to preach and really good at it, you should read Msgr. Charles Pope’s “homily notes” on the Archdiocese of Washington (D.C.)’s Communion in Mission blog. You can also subscribe to his YouTube channel, and on the same site you can also subscribe to the recorded homilies of Fr. Jay Scott Newman of St. Mary’s Catholic Church, Greenville (NC). Fr. Newman also has an interesting new blog on Substack, called The New Catholic Reformation, which you can subscribe to at no cost.

Speaking of blog subscriptions, if enjoyed this post, please subscribe and recommend it to your friends!