THERE IS A PROMINENT STRAND uniting many of the books that I have planned for my Nova & Vetera editions, and that is the English spiritual tradition. Some of these titles will be from the “post rupture” period (i.e., after Henry VIII forcibly took over the Church in Great Britain and outlawed worship faithful to Rome), while others will be taken from the “pre-rupture” period, when the English practiced the same faith as other Christians throughout Europe, with free interchange between the Continent and the British Isles.

One of the things I'd like to show in bringing these books back to modern readers' attention is that, despite the struggle to re-appropriate the English Church for the Crown and to refashion it according to novel and competing theologies, there was something deep in the English spirit that resisted this kind of manhandling. These are, chiefly, the spirit of monastic life and the mystical, or contemplative, life.

Reconnecting England's History and Tradition

In the nineteenth century, several things occurred that encouraged the English people to reconnect with their past, from which they had been effectively severed for three centuries: first, the cessation of official (legal) hostility toward the practice of the Catholic faith, and, more or less concurrently, a revival of interest in the “Catholic” aspects of English Christian faith and practice (the Tractarian and Oxford movements) encouraged some Anglicans to reconsider what had been lost when the Church of England was cut off not only from the Catholic Church but also from their own history as a Catholic nation. The same period saw the rise of modern scholarship, which focused on studying, editing, and publishing ancient texts that had been gathering dust for centuries in private and university libraries here and there. Many such texts were re-published in the latter nineteenth century for the first time in hundreds of years—some of them had been completely forgotten and thus were rescued from oblivion, thanks to both modern scholarly interest and modern print production.

Rediscovering Julian of Norwich

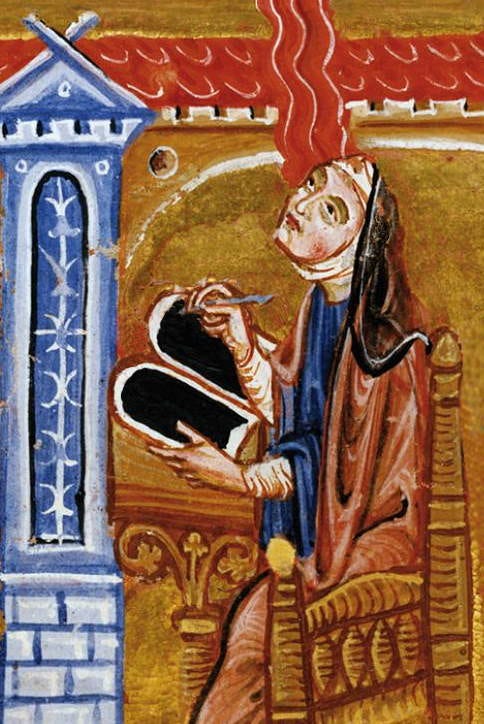

This was the case with the first book in the English Spirituality series that I will publish: the original (shorter) version of Julian of Norwich's account of a series of mystical apparitions and inner locutions that she experienced as a young woman in the latter years of the fourteenth century. The longer version of her account incorporates a theological “unpacking” of that experience, the fruit of decades of meditation on her experiences which was written, apparently, near the end of Julian's life (d. circa 1416). This long version, which survives in several medieval manuscripts, is pretty well known today under the title Revelations of Divine Love, sometimes known as her Shewings, because of what Christ showed her in her visions.

The original, shorter version of Julian's account, however, has survived in only a single manuscript, which was rediscovered in 1910 when the private library to which it belonged was sold at public auction. A scholarly clergyman named Dundas Harford almost immediately (1911) brought out an edition of this shorter version, under the title Comfortable Words for Christ's Lovers—the only publication of this original text for many decades thereafter. This short work remains barely known today, which is one reason I think it deserves to be brought back to the attention of the public.

Another reason for republishing this version is simply that, when it comes to a anything written in the fourteenth century, modern readers are more likely to try a short book than a long one. But I also find that this short text, which probably represents Julian's earliest effort to capture her experiences for posterity, preserves the freshness of her visions and allows the reader a more immediate experience of them. While I hope that reading this short text will encourage some readers to go on to read the longer version, in which we get the benefit of the author's years of meditation on the meaning of what was shown to her, I find that the absence of a lot of theological commentary makes the shorter text more accessible as a work of devotion. We can read a single short chapter and then spend time in our own reflections as we meditate on what Julian's account reveals to us.

[If you'd like to know more about this book, follow the Learning God series that begins here, and be sure to subscribe below to get new posts as they appear.]